Why Scale Weight DOES Matter

I was eight years old the first time I learned about calories.

I remember I was standing in the kitchen of my best friend’s home at the time, and we were happily sharing a bag of flaming hot Cheetos.

“Do you know what calories are?” M asked me. She went on to explain how a calorie was a way to measure how much energy was in food. She’d overheard her mother discussing them over the phone the other day. The higher the number, the more calories something had. Seemed simple enough.

I glanced down at the nutrition label of the Cheetos bag I was holding and tried to decipher the text. I’d never even noticed the label on food before then; I had simply eaten what had tasted good. It had never crossed my mind to consider the energy content of my meals. (And honestly, who could blame me? I was just learning to master the multiplication table.)

One hundred sixty calories per serving.

What?!, I remember thinking. Wow, 160 calories – that seems like a lot.

I looked at M and proclaimed, “This has way too many calories!” and she nodded in agreement with fear in her eyes.

“Is that bad?” I asked. She looked at me, a little unsure, and conceded that maybe… maybe not… but she wasn’t positive. Maybe we should stop eating – you know, just in case.

Remember, I was eight years old back then. I had just learned about what calories were (kind of), but wasn’t provided with the proper context with which to interpret them. I didn’t know that 2,000 calories per day was supposedly an average adult’s calorie intake and that I ingested upwards of 3,000 calories per day at the time (as an active, growing child, I had a voracious appetite). I had no clue that 160 calories per serving for a snack was actually very reasonable.

All I knew was that 160 in general seemed like a very high number to me. Heck, my age was still in the single digits, and I weighed maybe 60lbs soaking wet. Of course 160 was going to seem high.

So I saw a number and freaked out. I panicked.

As I grew older and became more familiar with the concept of calories, I realized that I had simply been uneducated and hadn’t had the proper knowledge to make sense of the numbers on the nutrition label. It became clear to me that there was actually no reason for alarm.

I knew better.

When it comes to scale weight, we as adults behave in much the same way.

Many of us don’t fully understand what the number means, and we base our beliefs regarding scale weight largely on what the media tells us.

Higher number is bad; lower number is good.

(For men, oftentimes the inverse is considered to be true.)

But I have a problem with that.

When we are properly educated, the scale weight can actually be an incredibly valuable tool to gauge health and fitness progress.

Below I’ve done my best to present a neutral, objective case both for and against frequent self-weighing, followed by my thoughts on how we should treat scale weight overall.

Arguments for Frequent Weighing

Frequent self-monitoring can improve self-awareness by alerting the individual to subtle weight increases that can then be nipped in the bud via dietary and exercise intervention (Wing et al., 2006). In other words, if you’ve been happily minding your own business but wake up one day 8lbs heavier than your usual weight after a weekend of particularly heavy imbibing and snacking, that may spur you into feverishly chomping down veggies and hitting the gym to bring that bodyweight back down.

It can be surprisingly difficult to notice weight gain over time, particularly when you’re focused on other aspects of your life, such as a new love interest or a demanding school schedule. One of my friends from high school recounted the story to me of how he piled on 30lbs during his freshman year of college and legitimately didn’t even notice until he returned home for winter break. I also have a female friend who told me that in her first year of married life, she slowly put on 15lbs and had no idea until she went to the doctor’s for her annual checkup. And it’s not just her; this inability to recognize weight gain was observed in a 2012 of 466 women of various ethnicities (Rahman & Berenson, 2012). If you’re not paying attention, this can absolutely happen to just about anyone.

Frequent self-weighing is one successful component of maintaining long-term weight loss (Mcguire et al., 1999). In fact, recent systematic review from 2014 found that the following were critical components for significant safe weight loss maintenance: an energy deficit, physical activity, and behavior training, including self-monitoring and educational programs (Ramage et al.). What’s interesting to note is that despite popular belief that weight loss maintenance requires an entirely distinct set of strategies, this observation was not made in this review. In other words, the same three strategies – energy deficit, physical activity, and behavior training – were crucial to successful weight maintenance over the long-term.

Is ignorance truly bliss? I’m not so sure.

Arguments Against Frequent Weighing

For some individuals, frequent self-weighing can contributed to increased body dissatisfaction and lower self-esteem, particularly when weight loss is slow or failing(Dionne & Yeudall, 2005). As well, increases in depressive symptoms are associated with weight gain, as are increased disinhibition, hunger and restraint (Wing et al., 2005).This makes sense, particularly if we’ve been taught to believe that we are valued more highly the less we weigh. Couple this with today’s culture of instant gratification, and you can see how the situation could get really ugly really fast.

Female adolescents in particular seem to be especially prone to binge eating and other disordered eating behaviors in association with frequent self-weighing (Neumark-Sztainer et al., 2006). Contrast this with male adolescents, with whom it appears that self-weighing does not give rise to unhealthy weight control behaviors. It’s clear that female adolescents tend to care more about how much they weigh and are more preoccupied with weight loss strategies (Neumark-Sztainer et al., 2002). This dichotomy is likely due to discrepancies in societal expectations, wherein women are generally expected to be thin to be considered beautiful while men desire a more muscular build.

It doesn’t measure self-worth, competence, intelligence, or personality. Yet so often, we equate these intangible qualities to some arbitrary number on the scale. What a true mindf*ck this can be!

It appears, then, that the primary argument against stepping on the scale is that it can be psychologically harmful. After all, many individuals – women in particular – are prone to tie self-worth to the number on the scale, and it’s all too easy to allow some random digital blinking number to determine our mood for the day.

Never mind the fact that scale weight in isolation tells us next to nothing save for, quite literally, the sum total of the mass we are carrying. That’s it. Nothing more. (See related: Why Relying Solely on Scale Weight is a Losing Strategy)

Sohee’s Thoughts

The research surrounding scale weight and its relationship with potential adverse psychological effects is mixed. Some studies suggest that frequent self-weighing is inherently harmful, while others, including a 2007 study by Wing et al. involving 314 participants, find no harmful psychological effects.

Huh.

Here’s my take: The majority of us are not properly educated when it comes to how to make sense of scale weight. Some of us have likely grown up watching our mothers step on the scale in trepidation and either breathe a sigh of relief or break down in tears. It’s hard to forget that kind of stuff. This is a big part of why we have such varying reactions to the scale: some of us are completely neutral, while others need to weigh themselves several times per day, and still others eschew it altogether.

The problem is that the relationship between scale weight and psychological constructs such as body image is poorly understood.

I’m not convinced that proclaiming that the scale is the devil and should be thrown out forever and ever Amen is the healthiest strategy. After all, is this not simply a form of avoidance behavior?

This scenario is not unlike trying to banish cookies from your diet forever because you don’t know how to stop at just one. Again, avoidance behavior. The biggest issue is that this is life. You can try to avoid it all you want, but sooner or later, you’re going to be confronted with a plate of cookies – at a get-together or a social function of some kind – and you’re not going to be equipped with the tools you need to skillfully navigate the situation with grace. Because avoidance. In fact, you’ll likely be a blubbering, heaping mess of nerves.

Doesn’t sound very fun or very practical, does it?

With the scale, it’s much the same way.

So how about instead of giving the scale the power over our emotions and our thoughts, we take charge?

I want to use myself as an example of how scale weight can be used for good.

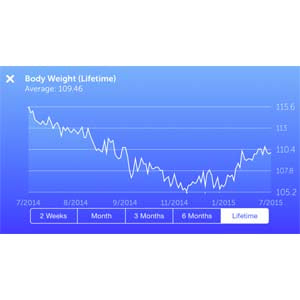

Above is a graph showing my change in bodyweight since late June 2014. As you’ll notice, I started out at approximately 116lbs (I am 5’2″). I then embarked on a 20-week contest prep and stepped on the bikini stage in November at 106lbs. After that, I reverse dieted my calories back up to between 1,800-2,000 calories a day and also switched gears to powerlifting from January to May of 2015. Since then, I’ve dropped my calories back down a bit to approximately 1,600 a day and have been hovering in the 109-110lb range.

Here are some pictures of me during the main time points:

This is the front starting picture I sent over to my coach last summer at the beginning of my bikini prep. By then, I’d been lifting heavy for 6.5 years and, while I had counted macros on and off, at the time I only loosely tracking my intake.

For my prep, my workout regimen consisted of four days a week of strength training coupled with two days a week of high intensity intervals. I followed a macros-based approach with high protein (just above 1g/1lb total bodyweight) plus higher carbs on training days and lower carbs on off days.

Here’s what I looked like when I competed four months later. By the time show day rolled around, I was strength training five days a week and my cardio was bumped up to three days of high intensity intervals. As well, my total calorie allotment had dropped a few hundred calories from my starting point.

During the course of this prep, I lost over 2 inches off my waist and leaned out pretty evenly all over. I followed both my training and nutrition programs to the letter and tracked not only my daily macronutrient intake but also my changes in bodyweight and body circumference measurements over time.

I fortunately did not lose much strength in the gym, but I distinctly remember feeling rather skinny, and I knew that that was not a look that I wanted to maintain year-round.

In the months following my show, we carefully raised my calories back up. Interestingly, my bodyweight continued to drop for some time even after the competition despite consuming more food. You’ll see in the graph above that I dipped into the low 105’s on a few occasions. (I should note here that at no point in time did I ever engage in extreme measures to achieve these kinds of results.)

In January 2015, I continued to raise calories and then eventually weaned myself off of macro counting for a number of months. During that time, I also switched up my training to prepare for my first ever powerlifting meet. My instructions from Bret Contreras, who took me under his wing for this prep, were to simply keep an eye on the scale weight and monitor my eating accordingly such that I’d be able to make weigh-ins for the 105lb class. My bodyweight hovered in the 108lb range for the majority of my powerlifting prep, and I ended up having to drop just a few pounds of water weight in the final week leading up to the meet in May.

This is the most recent progress picture of me. I’m eating a good deal more than I was back in November and I’m looking a little more athletic. I’m far stronger than I was before, and you’ll notice that I’ve put some quality lean body mass as well. Overall, my body composition seems to have improved a tad.

I’ve also increased my training volume from what I was doing back in the spring when preparing for the powerlifting meet. I’m still working hard as hell, but now I’m setting PRs every week in the higher rep ranges. This, coupled with my return to meticulous macro tracking, has attributed to the improvements in my physique.

Over the past month, my macronutrient intake has not changed, and I’ve been sleeping just as soundly as ever. (It’s worthing noting as well that we are actually keeping me at maintenance calories – or at least, our best estimation of it – so the goal is not to actively shed fat at this time.) The only thing that’s been changing from week to week has been my training numbers. I’m setting PRs in virtually every session – my front squat has gone from 65lbs for 8 reps on June 15 to 96lbs for 6 reps on July 20, for instance, and my close grip bench press has increased from 65lbs for 10 reps on June 8 to 80lbs for 9 reps on July 20 – and as a result of that, we’re noticing subtle changes to my physique. And interestingly, my body circumference measurements have not budged at all, but my bodyweight has gone up a pound.

What does this mean? Likely a small increase in lean body mass. And given all the above variables, there’s no cause for concern. After all, how is increasing strength and improved body composition anything to cry about?

Going off of scale weight alone, you wouldn’t know any of these things. Nevertheless, it’s a valuable tool that can shed some light on where your fitness may be headed when you take it into context. In my case, since we are controlling for all other factors, it appears that the increase in scale weight is indeed a reflection of extra LBM. I’m intrigued to see how my bodyweight continues to fluctuate, if at all, over the next few months.

Here’s how I feel about the drop in scale weight last year:

And the increases this year:

Okay, enough of being facetious.

The point I’m trying to make is this: I’m not doing backflips and lighting fireworks when I’m lighter, and I’m not sobbing on the floor when I’m heavier. What good does that do?

I know I lost weight because I was eating at a caloric deficit. And this time around, the scale weight has been inching up because I’ve been gaining lean body mass. Great! Wonderful!

Moving on.

When it comes to physique aspirations, we’re better off shooting for a goal look rather than a goal weight.

If I look in the mirror and like how I look, why would I let some number on the scale bring me down?

How Should We Treat Scale Weight?

It seems, then, that the general consensus is this:

No one would have a problem with the damn scale weight if it wasn’t such a mindf*ck.

Right?

Okay, that much has been established.

But why is it that some people can step on the scale no problem and then proceed to move on with their merry day, while others become an emotional train wreck? I would venture to guess that this has a lot to do with an individual’s upbringing and what he or she has been taught – in the immediate home environment, in the social setting, as well as from mass media – about how to interpret scale weight.

How much self-weighing is too often? Again, this depends on the individual. Scale weight will mean something very different for an elite-level athlete trying to make weigh-ins for, say, a wrestling match versus a layperson who simply wants to stay healthy and is fine with maintaining measurements.

As we’re coming to learn, we cannot separate physiology from psychology (though it sure as hell would be nice!). We get emotional. We get upset. We have body image and self-esteem to consider. And these things absolutely matter, and they absolutely cannot be overlooked when we’re thinking about our long-term health.

Context matters.

Be proactive, not reactive, about scale weight.

If you’re nailing your nutrition and crushing your workouts but your sleep has been poor and your stress has been high, scale weight will likely go up. It doesn’t mean you’ve gained fat necessarily, and it doesn’t mean that you’re “failing” in your fitness goals. You probably just need a full night’s rest and a little bit of stress relief and scale weight will go back down.

By the same token, if your sodium intake spikes one night, don’t be surprised if you’re retaining a few extra pounds of water the next day. Again, that doesn’t mean it’s fat.

Before your emotions kick in, ask yourself: Is there anything I did yesterday outside the norm that may be influencing the number on the scale today? And be as objective as possible about the number blinking back at you.

If it is the case that scale weight has gone up as a direct result of your increased caloric intake as of late and you are undeniably carrying more bodyfat than before, then okay. Be an adult. Do something about it, but be gentle with yourself. No negative self-talk, no beating yourself up. Just do what needs to be done to get things moving in the right direction again.

Don’t view scale weight in isolation.

(Are we seeing a theme here, perhaps?) A 6’2″ sedentary man who does not strength train regularly and weighs 220lbs is going to be very different from a man of the same height and weight who trains for physique competitions.

Scale weight is simply one factor of many (including but not limited to: total calorie intake, macronutrient intake, sodium consumption, stress, sleep quantity and quality, digestion, and menstrual cycle) that can help assess health and fitness.

Part of the problem I’m finding is that with research, there has yet to be a single study conducted on resistance training, macro-counting (or at least, calorie-conscientious) fitness buffs who are proactive about cultivating the right mindset for health. (If there is such a study out there, I’d love to see it!) And I doubt that any kind of study will be carried out anytime soon, unfortunately.

We wouldn’t have an issue with scale weight if we were properly educated as to how to interpret the number.

Can you go to the doctor’s office for your annual physical and not have a meltdown when you’re instructed to step on the scale? Can you have someone ask you your bodyweight (for, let’s say, a powerlifting meet) and not have you lose your cool? If so, you’re doing quite well.

Scale weight is simply another data point. It’s just a number.

As my friend and colleague Coach Stevo says,

View scale weight with as much emotion with which you’d count the number of white cars in a parking lot.

In other words, take the damn emotion out of the equation.

Yes, yes, the number on the scale says nothing about who you are as a person – no one is arguing that.

No, it’s not useless. It can actually be very telling about what’s going on with your body.

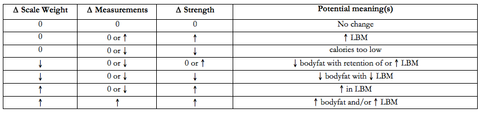

Here is an admittedly rudimentary table I’ve put together that can serve as a starting point to help you make sense of what the scale weight might mean. For the sake of simplicity, this table is based on a number of assumptions: solid dietary adherence, sound management of sleep and stress levels, consistent sodium intake, and sound training program based upon the principles of progressive overload. In other words, I’ve controlled for as many variables as possible. Please keep in mind that there will of course be exceptions to just about every rule.

Please don’t misunderstand me: I’m not saying that everyone has to start weighing themselves everyday or even every week for that matter.

Hell, you don’t have to weigh yourself frequently at all, just so long as you have a healthy relationship with the damn scale.

How often you choose to weigh yourself is, quite frankly, none of my business, and is also besides the point.

But much like my story above of my naïveté regarding the concept of calories, making sweeping and well-intentioned yet unfounded claims about the scale can do more harm than good in the long run. This reminds me a lot of the scene in Finding Nemo where the fish believe that a boat is called a “butt” – and very mistakenly so. I think it’ll be pretty clear to see with this analogy how misinterpreting and misunderstanding a concept helps no one.

I know that fostering the right attitude takes time. It’s by no means an overnight process. I get that – oh boy, do I ever!

But phew, can we at least take one small baby steps in the right direction?

Can we stop making the scale weight a scapegoat and instead be completely, brutally honest with ourselves?

Context, context, context.

References

Dionne, M.M., Yeudall, F. (2005) Monitoring of weight in weight loss programs: a double-edged sword? J Nutr Educ Behav. 37:315-8.

Helander, E. E., Vuorinen, A.L., Wansink, B., & Korhonen, I.K. (2014) Are breaks in daily self-weighing associated with weight gain? PLoS One. 9(11):3113164.

Korotitsch, W.J., Nelson-Gray, R.O. (1999) An overview of self-monitoring research in assessment and treatment. Psych Assess. 11(4):415-25.

Klos, L.A., Esser, V.E., & Kessler, M.M. (2012) To weigh or not to weigh: the relationship between self-weighing behavior and body image among adults. Body Image. 9(4):551-4.

Linde, J. A., Jeffery, R. W., French, S. A., Pronk, N. P., & Boyle, R.G. (2005) Self-weighing in weight regain prevention and weight loss trials. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 30:210-16.

McGuire, M.T., Wing, R.R., Klem, M.L., & Hill, J.O. (1999) Behavioral strategies of individuals who have maintained long-term weight losses. Obes Res.7(4):334-41.

Neumark-Sztainer, D., Story, M. Hannah, P.J., Perry, C.L., & Irving, L.M. (2002) Weight-related concerns and behaviors among overweight and nonoverweight adolescents: implications for preventing weight-related disorders. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 156(2):171-8.

Neumark-Sztainer, D., van den Berg, P., Hannan, P.J., & Story, M. (2006) Self-weighing in adolescents: helpful or harmful? Longitudinal associations with body weight changes and disordered eating. J Adolesc Health. 39(6):811-8.

Rahman, M., Berenson, A.B. (2012) Self-perception of weight gain among multiethnic reproductive-age women. J Women’s Health. 21(3):340-6.

Ramage, S., Farmer, A., Eccles, K.A., & McCarger, L. (2014) Healthy strategies for successful weight loss and weight maintenance: a systematic review. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 39(1):1-20.

Wing, R. R., Rate, D. F., Gorin, A. A., Raynor, H.A., & Fava, J.l. (2006) A self-regulation program for maintenance of weight loss. N Engl J Med. 355:1563-71.

Wing, R. R., Tate, D. F., Gorin, A. A., Raynor, H.A., Fava, J.L., & Machan, J. (2007) STOP regain: are there negative effects of daily weighing? J Consult Clin Psychol. 75(4):652-6.