Strength Gains are Not Linear

You can’t expect to put 10lbs on your squat every single week.

While that would be nice in theory, that means that if I were to start out with a 95lbs squat on January 1st, by the end of the year, I’d be going 615lbs rock bottom. Somehow, I don’t think that’s very likely.

Strength gains are not linear. This is a point that I find hammering home to my clients over and over. Just because you find yourself struggling with a particular weight this week that flew up last month, it doesn’t necessarily mean that you are losing strength. It’s not immediate cause for concern.

Factors That Influence Strength

If strength were to occur in a vacuum, then perhaps gains in the gym would be more linear. How awesome would it be to increase your deadlift by 520lbs in one year, after all? However, life happens, and there are a hundred and one different variables that influence strength.

The most obvious factor to begin with: training experience. In general, beginner trainees will be able to see some pretty rapid strength gains in the first few months of a resistance training protocol. It’s not unusual to see upwards of 10+ pounds slapped onto the barbell per week during this time as the body becomes more coordinated and more practiced at a given exercise. This is not so much due to actual strength increases so much as neuromuscular adaptations taking place. Then, as you approach six months to a year of regular training, strength increases will necessary slow down. By the time you’re a veteran lifter with 10+ years under your belt, PRs will be hard to come by and incremental at best, and you’ll have to put in more and more work for increasingly diminishing returns. The sooner you realize this, the less disappointed you’ll be.

Next, we have caloric intake. If you’re in a caloric surplus (meaning that you’re consuming more energy than you expend), then you have extra fuel available to push it harder in the gym and set PRs. Conversely, being in a caloric deficit will probably mean that strength gains are harder to come by – though if you are following a sound training program, some strength gains can still be expected, especially at the beginning of a fat loss phase.

We also have to take into consideration training program specifics. How is your program structured? What movements are prioritized, with what sets and reps? How much rest are you taking in between working sets? (Remember, longer rest lends to better strength gains.) Are your workouts designed with strength as the main goal, or are your sessions haphazard, with every week being different than the one before?

Obviously, training program specifics are irrelevant if you don’t pay attention to training intensity and progressive overload. Performing 2×5 back squats doesn’t mean much without appropriate context. Are you simply going through the motions, or are you lifting as heavy as possible within a prescribed rep range while using solid form? (The answer, in most cases, should be the latter.) You can make any given set as easy or as difficult as you decide to make it, depending upon your intensity. If your goal is to gain strength, then you should be utilizing progressive overload and actually doing the things you need to do to, uh, get stronger. Investing in a training journal to log your workouts can help tremendously in this endeavor.

What working set numbers won’t tell you is when you have a variation in form. This can include increasing or decreasing range of motion, fiddling with your stance, improving neutral spine, finding a better hand position, and so on. This actually circles back to the point on progressive overload above, because if you’re squatting the same amount of weight as you were a month ago but you’re going four inches deeper, you’ve certainly progressed in that lift. So while on paper, 135lbs may seem like 135lbs, you should always note when your form is different in any way.

We also cannot overlook the role of sleep, hydration, and general energy levels on any given day. If your significant other kept you up late last night with his snoring, then you probably won’t have the most stellar workout today and your numbers may be rather lackluster. If you’re dehydrated, even losing a mere 3% of your bodyweight in fluids can be enough to negatively impact performance. And of course, sometimes, despite firing on all cylinders, you simply won’t have it in you and your energy levels will be lousy.

We should also talk about genetics. Why? Because people like to think that genetics don’t matter and hard work trumps all. For better or worse, genetics do influence not only our baseline levels of athletic ability but also the rate at which we are able to gain strength and muscle. Think about that chick you follow on Instagram who’s been lifting for two years and is already setting powerlifting records left and right, seemingly on accident. Then compare that with someone like little ‘ole me who’s been resistance training for over eight years and has the most mildly, mildly impressive numbers. It’s not she’s trying harder in the gym than I am. The stark discrepancies can be attributed to differences in satellite cell, mechanogrowth factor, myogenin, and IGF activation, amongst others.

Finally, it could be the case that you’ve actually lost true strength. This can happen when you don’t train a particular movement for a while, when you’re in a steep caloric deficit for an extended period of time, and/or when you take a hiatus from the gym (due to vacation, injury, etc.). Usually, it’s pretty clear when a strength decrease isn’t just a fluke – your numbers stay down week after week rather than bouncing back at your next workout, and weights that used to fly up during your warmup consistently feel markedly heavier.

Charting Strength Gains

To illustrate my point, I’m going to use myself as an example. For the sake of simplicity, I’ll walk you through my progress in the big three lifts (squat, bench, and deadlift) over the past year.

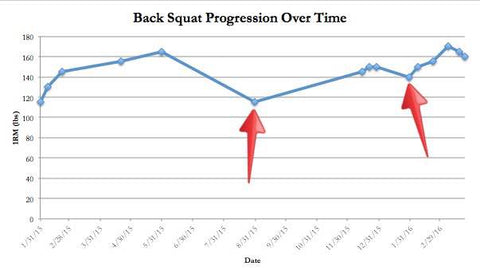

Back squat

A glance at the chart below might have you thinking that I got stronger last spring, then completely tanked in the summer, worked my way slowly back up over this past winter, and then dropped again around New Year’s. I’ve pinpointed two specific areas of interest that are worth discussing.

From January through late May of last year, I was preparing for my first ever powerlifting meet. Admittedly, I hadn’t back squatted for several years, so my strength gains for the first several weeks were pretty rapid (not unlike that of a beginner trainee). The increases in my 1RM can also be attributed to switching from high bar to low bar and overall improving my form over repeated, practiced sessions. My numbers started to slow in the late February/March timeframe when I began experiencing some pretty bad hip pain from squatting three days per week following a Daily Undulating Periodization protocol. I took a week off of squatting altogether and then was able to return to squatting once every five to seven days pain-free, albeit with greatly reduced volume. I ended up hitting 165lbs at my 100% Raw powerlifting meet at the end of May.

For the next few months after, I moved away from back squats and threw higher rep front squats into my routine. There really wasn’t much carryover from my front squat high rep strength to my back squat strength, unfortunately (lesson learned and duly noted for the future). To add fuel to the fire, I took a trip to Italy in August which resulted in a 10-day break from heavy resistance training. By the time I returned home, my 1RM had plunged to 115lbs (first arrow). Yep, talk about serious detraining.

My back squat is not my forte to begin with. Throw a six-week bikini prep into the mix over the fall (entailing a caloric deficit) and a temporary shift away from a powerlifting-focused program, and it took me longer than I care to admit to simply get back to my baseline strength.

Regarding the second arrow, right around early February of this year was when I learned that the USAPL federation, which I had switched into, was far stricter on squat depth. That meant that going to parallel with 165lbs was not going to cut it, and I was forced to scale way back on weight in order to sink depth with my working sets.

Note the marked difference in depth between last year’s powerlifting prep:

145lbs x 1

And this year’s prep:

140lbs x 3

https://www.instagram.com/p/BDhUeOwThwO/?taken-by=soheefit

In the first video, I’m going just to parallel, and this is the same depth I hit 165lbs with at last May’s meet. In the second video, I’m sinking well below parallel, so while the absolute weight on the bar is lower, I’m not only getting better depth but also squeezing out more reps with ease. I should note as well that the above set of 140lbs for 3×3 was a submax effort.

Looking at nothing but absolute training numbers doesn’t tell the whole story, as you can see. With regards to my back squat, we can attribute the fluctuations in 1RM to actual strength loss (first arrow) and intentionally scaling back weight to improve form (second arrow).

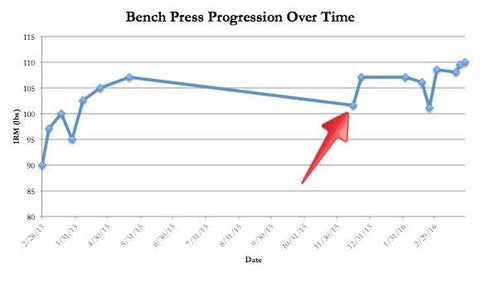

Bench press

Before I dive into an analysis of my bench press progression, it’s important to clarify two points: 1) for powerlifting, the bench press involves a pause at the bottom of every rep, so it’s not touch and go, which means that weight is usually lower due to the increased time under tension; and 2) strength increases in upper body movements are necessarily slower than that of lower body movements, so even a 5lb bump over the course of several months can be a pretty big deal.

Through the first few months of last year, you can see a relatively quick increase in strength – again, this is due to neuromuscular adaptations and becoming more efficient with form. Up until that point, I had pretty much spent the past seven years of strength training sticking to the dumbbell bench press or incline bench press as my upper body horizontal pressing movements of choice.

You’ll see that my strength dips right around late March. I don’t have it noted in my training journal unfortunately, but this can likely be attributed to poor sleep, shoddy nutrition, or just subpar energy levels from that day. Notice, though, how the following week, my bench comes back up and I manage to set a PR. The same thing happened this year in mid-March – what should have been an easy 105lbs for me ended up being an ugly, grindy rep, and I was forced to conclude my working sets there. Bummer.

https://www.instagram.com/p/BDCPobfTh7x/?taken-by=soheefit

However, the following week, I came back and set a PR of 108.5lbs and then 110lbs a couple of sessions later.

https://www.instagram.com/p/BDhCpdNzhy1/?taken-by=soheefit

It’s not unusual to have a mediocre session one day and then knock the exact same exercise out of the ballpark a few days after.

The drop in strength from May to November of last year (see arrow) is simply due to lack of training specificity. During the summer months, I stuck primarily with incline bench press and close-grip bench press in the higher rep ranges (6-15). The good news, though, is that when I circled back to low rep pause bench press, I hadn’t lost all of my strength, and my 1RM was still a good bit above where I was when I first started. So while the graph may seem to indicate strength loss, this is actually a net win.

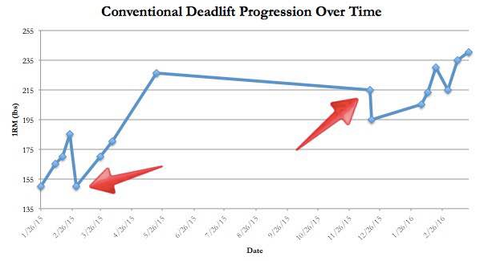

Conventional deadlift

Finally, we have conventional deadlift. Though technically this is my best (relative) lift of the big three, it’s also the one that I’ve wrestled with the most with my form. I’m far stronger as a round back puller, you see, and carefully toeing that line between continually getting stronger in preparation for a powerlifting meet while simultaneously not overdoing it and increasing my risk for injury has been quite the balancing act.

My 1RM last January was 150lbs. You’ll notice that in the video below (my very first powerlifting workout ever!), I was actively trying not to round, but I still was not able to maintain a completely solid arch. The barbell also rolled away from me right before I pulled, which is far from ideal.

I continued in this manner until March, when my trainer Bret Contreras warned me that I was starting to round my back a little too much. The first red arrow is when we stripped weight off the bar so I could stick with arch back pulling.

Between March and late May of last year, I learned to get comfortable using a lifting belt, I gained confidence in my pull, and I got the OK to round back again as we neared the meet. I slapped on 50lbs to my deadlift in a matter of weeks and hit 226lbs at my meet. Fun stuff!

https://www.instagram.com/p/3UrGyrThwW/?taken-by=soheefit

Over the summer, I switched to block pulls and other deadlift variations to mix things up. Interestingly, even while I dieted down for my bikini show, my pulling strength remained largely intact. By the time I returned to training like a powerlifter in late December, my 1RM was still pretty freakin’ solid (as noted by the second arrow) and from there, my numbers have only continued to move in an upward trend. The small dips in numbers you see in the graph above are from training in a different gyms (and therefore being in a different headspace mentally), and another time I tried to deadlift shortly after waking up from a nap. It turns out that naps and deadlifts don’t pair together quite so well for me! Still, despite the ups and downs, I most recently hit a 240lb pull with relative ease.

https://www.instagram.com/p/BDRkFKXzh9t/?taken-by=soheefit

Focus on Long-Term Trends

In all three graphs above, you’ll notice the following:

- The strength increases are by no means linear – not even close! In fact, there are periods of time where it looks like I’m actually getting weaker. As discussed above, I actually did lose true strength in my back squat last summer, but the bench and deadlift trends could be explained by lack of training specificity.

- As a whole, I’m still stronger across the board now than I was a year ago, and that much is undeniable.

It’s not worth getting upset over one mediocre session where you couldn’t lift as much as you did two weeks ago. It doesn’t always mean that you’re actually weaker; it may simply mean that today wasn’t your day.

Some weeks you’re going to feel invincible, and you should absolutely take advantage of these times to enjoy your workouts, set incredible PRs, and gain confidence in the gym. Every now and then, however, you may fall into a rut and you’re just not going to have it in you. Oftentimes, there will be an obvious reason that can explain your ho-hum training numbers for the day, but sometimes you’re going to do everything right and still fall flat on your face.

This is okay. Take it all in stride.

Rather than throwing a tantrum over one isolated workout, take a step back and focus on long-term trends. Are you stronger than you were three months ago? How about six months ago? A year? The answer, if you’re been consistent with your workouts and diligently putting in solid effort, will most likely be yes.

Celebrate that.