10k Steps a Day: Legit or Myth?

For as long as I can remember, health professionals, coaches, fitness enthusiasts, and everyday people have been touting the idea that 10k steps per day is the gold standard.

But is this the case, according to science?

Read on.

Where Did the 10k Steps a Day Recommendation Come From?

The blanket recommendation for everyone to hit 10k steps a day for optimal health has become widely accepted in recent decades.

But in reality, this advice actually began as a marketing tactic.

Back in the 1960s, a campaign to sell more pedometers was launched in Japan, and the message was to hit 10k steps a day. It’s even said that the Japanese character for 10,000 looks a little bit like a person walking.

Aided by the fact that 10,000 is a nice, neat number, this recommendation has been repeated so many times since then that it’s practically become gospel.

This means that the origins of “10k steps a day” were never based on scientific evidence.

In recent years, many coaches and health professionals (myself included) have aimed to address the misconception that 10k is the golden number of steps that everyone should hit each day.

Some people have claimed that those of us who have been questioning the 10k number are trying to discourage people from being physically active. This couldn’t be further from the truth.

Let me make it abundantly clear that the general message behind the “10k steps a day” recommendation – that physical activity is good for you – is something I absolutely support. But this topic is so much more nuanced than “10k steps should be the standard for everyone.”

What the Research Says

Here’s the reality.

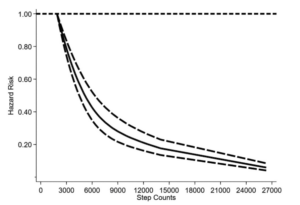

Liu et al. 2022 found that people with the highest step count of 9,994.3 steps/day (essentially 10k) or more had a 75% lower risk of all-cause death than those who averaged 4,000 steps/day. After viewing this data, it’s easy to make a surface-level conclusion that everyone should aim for 10k steps a day no matter what. But what many people fail to acknowledge is the following:

Compared to the lowest step count of 1,895 steps/day, for all causes of death:

- 4,000 steps/day had a 37% lower risk

- 6,388 steps/day had a 60% lower risk

- and 9,994.3 steps/day had a 75% lower risk

You can see from the above graph that the steepest changes in hazard risk occur around the 7,500 steps/day mark, which is supported by Lee et al.’s 2019 findings.

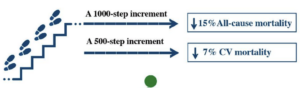

A more recent meta-analysis (Banach et al. 2023) also found a dose-response relationship between daily steps and decreases in all-cause and cardiovascular mortality.

Specifically, a 1,000-step count increase correlated with a 15% reduction in all-cause mortality, and a 500-step count increase correlated with a 7% reduction of cardiovascular mortality.

The authors wrote: “[a]s little as 4,000 steps/day are needed to significantly reduce all-cause mortality, and even fewer steps are required for a

significant reduction in CV deaths.”

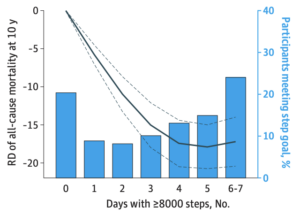

Furthermore, Inoue et al. 2023 examined the impact of walking intensively only a few days a week rather than every day. The researchers found that participants “who took 8,000 steps or more on just 1 or 2 days of the week showed a substantial reduction in all-cause and cardiovascular mortality compared with those who were active more regularly (i.e., took 8,000 steps for 3-7 days per week).

They also noted that those with higher step counts tended to be (amongst other things) younger, married, male, and less likely to have mobility issues, indicating that high levels of physical activity are often associated with more privileged populations.

Similarly, Lee et al. 2024 found that “weekend warriors” (people who exercise primarily on the weekends due to time constraints or other reasons) can still see meaningful improvements in mortality rates.

Are you starting to see the nuance?

The Problem with the Blanket “10k Steps” Recommendation

Now that you’ve had a chance to familiarize yourself with the research, let’s break down why the “10k steps a day” recommendation is problematic.

For starters, many of the people recommending 10k steps a day fail to include proper context. As a result, many people end up discouraged, believing that anything less is pointless and that they’ll reap zero health benefits unless they’re able to hit 10k steps on the nose every single day. As you can see from the ample body of research presented above, this is simply not true.

Further, much of the research done on daily step count and health outcomes are correlational in nature. This means we cannot establish a cause-and-effect relationship between steps and health. It’s entirely possible that there is a reverse causal relationship between the variables – namely, is it people who are already healthier who tend to take more steps, rather than the high daily step count leading to improved health outcomes?

There are also many legitimate, real-life reasons why hitting 10k steps a day isn’t always feasible. Some examples (among others) include poor neighborhood walkability and safety concerns, chronic illness, and disabilities. Insisting that everyone must hit 10k steps fails to account for these circumstances.

At the end of the day, step count is just one marker of physical activity. You could lift weights hard for an hour, and you’d rack up maybe a couple hundred steps during that time. You could swim for threehours, and all of that physical activity wouldn’t count towards a single step. Does that mean it isn’t worth doing? Of course not.

There are so many variables to take into consideration when it comes to our health, including but not limited to:

- resistance training / other movement besides walking

- sleep quality and quantity

- diet

- stress

- smoking and drinking

- chronic illness

- mobility/movement limitations

- social determinants of health

Thus, while staying physically active is definitely important across the board, it needs to be viewed within the context of all the other factors in someone’s life.

Practical Takeaways

Let me reiterate that physical movement is good. From the research, we know:

- There is a dose-response relationship between steps and mortality rates, so in general, more is better – with the most improvement seen with up to 7,500 steps a day.

- If you’re not very active, a small increase in daily activity can have meaningful benefits for your health, even if it’s not 10k steps.

- You don’t have to get in a super high number of steps every single day to reap the benefits of daily movement and activity.

Not everyone has the resources, time, or energy to hit the arbitrary “10k steps a day” recommendation, and that’s fine. We should instead be focused on setting flexible targets for ourselves that fit within the context of our lives.

We can encourage people to be more active without giving blanket recommendations that are generally unattainable for a host of very valid reasons.

If someone lives with debilitating joint pain, and it takes them 20 minutes just to get out of bed in the morning (and another three minutes to put on their socks), telling them to walk 10k steps a day doesn’t make sense. On a similar note, if someone works two full-time sedentary jobs and can’t go for a stroll in their neighborhood without fearing for their safety, recommending that they walk 10k steps is pretty inconsiderate.

Reaching 9,000 steps instead of 10k doesn’t make you a failure.

Going from 3,000 steps to 5,000 steps a day is a win.

Heck, going from 1,000 to 3,000 steps is something to celebrate, too.

I’m a huge proponent of doing what you can without overly stressing or compromising your quality of life to meet recommendations that aren’t catered to you.

Rather than telling everyone to “just try harder” or “have more discipline,” I would argue that it’s more effective to meet people where they’re at and recognize that, while getting in a lot of steps is doable and perhaps easy for some, we need to have more grace and stop pushing 10k steps as the default goal for everyone.

References:

Althoff, T., Sosic, R., Hicks, J.L., King, A.C., Delp, S.L., & Leskovec, J. (2017). Large-scale physical activity data reveal worldwide activity inequality. Nature, 547(7663), 336-339

Banach, M., Lewek, J., Surma, S., Penson, P.E., Sahebkar, A., Martin, S.S., … & Bytyci, I. (2023). The association between daily step count and all-cause and cardiovascular mortality: a meta-analysis. European journal of preventive cardiology, 30(18), 1975-1985

Jayedi, A., Gohari, A., & Shab-Bidar, S. (2022). Daily step count and all-cause mortality: a dose-response meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Sports Medicine, 52(1), 89-99

Inoue, K., Tsugawa, Y., Mayeda, E.R., & Ritz, B., (2023). Association of daily step patterns with mortality in US adults. JAMA Network Open, 6(3), e235174-e235174

Lee, I.M., Sesso, H.D., Oguma, Y., & Paffenbarger Jr, R.S., (2024). The “weekend warrior” and risk of mortality. American journal of epidemiology, 160(7), 636-641

Lee, I.M., Shiroma E.J., Kamada, M., Bassett, D.R., Matthews, C.E., & Burning, J.E. (2019). Association of step volume and intensity with all-cause mortality in older women. JAMA internal medicine, 179(8), 1105-1112

Liu, Y., Sun, Z., Wang, X., Chen, T., & Yang, C. (2022). Dose-response association between the daily step count and all-cause mortality: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Sports Sciences, 40(15), 1678-1687

Paluch, A.E., Bajpai, S., Bassett, D.R., Carnethon, M.R., Ekelund, U., Evenson, K.R., … & Fulton, J.E. (2022). Daily steps and all-cause mortality: a meta-analysis of 15 international cohorts. The Lancet Public Health, 7(3), e219-e228