Body Dysmorphia in the Fitness Industry

There was a time in my life – up until 15 years ago, I’d say – when I was completely uninhibited. For the most part, I said what I wanted, I wore what I pleased, and I engaged in activities that brought me joy. I didn’t worry about what others thought of me.

When it came to my body, I didn’t think twice. It was merely a physical vehicle that allowed me to carry my schoolbooks, sprint on the field, and embrace my loved ones. My body was my body. I surely did not waste precious energy fretting over the size of my thighs. It was a physical manifestation of me, yes, but it did not define me.

Until it did.

Many of you are familiar with my dark struggles with anorexia and bulimia – and if you’re not, you can read more about that here. That all started when I was 14 years old. As a young teen, I was not only dealing with the changes in my body, but I was also navigating my way through the painfully awkward time of many children’s lives that is better known as high school. That’s an incredibly impressionable age, you know; girls and boys alike start to care more and more about what the media deems to be hip and what fellow classmates are wearing, doing, and talking about.

Naturally, then, when some of my girlfriends first started discussing this formerly foreign concept of “dieting” and “needing to lose weight” and being “OMG so fat,” it piqued my curiosity. They all seem to care so much about how much they weigh… I guess I should, too. Seems logical, right?

I embarked on my first diet as a high school freshman. Whereas before, I was known for my voracious appetite, I was now surreptitiously skipping meals and pretending I was never hungry. And while the scale weight used to merely be a fun, harmless data point for me, I began to obsess over the blinking number every morning, and slowly but surely, it took control of my life. I became pals with hunger and best friends with the treadmill.

What’s heartbreaking is that to any other person, I looked like a regular, healthy teenager. But through my own eyes, all I saw were blemishes.

I couldn’t look at myself in the mirror the same way anymore, either. I became consumed with picking apart my physical flaws and finding spots that needed fixing.

I stared back at my reflection and couldn’t see me for me.

What is body dysmorphia?

As the term implies, body dysmorphia, or body dysmorphic disorder (BDD), consists of a preoccupation with one’s perceived or real physical flaws. This obsession is typically associated with an individual’s physique – flatness of the belly, size of chest, and so on – though one can also find fault with other body parts such as their hair, nose, or skin. Typically, even the slightest imperfection can cause severe emotional distress to an individual with BDD.

While it’s not uncommon for an average individual to dislike a few aspects of his or her body, BDD is characterized by intensely negative thoughts to the point where his or her life is crippled by this hang-up.

This reminds me an awful lot of TLC’s hit song, “Unpretty,” from back in the day. I’m sure some of you can relate to these sentiments.

The exact causes of BDD are unclear, though we can speculate to some of the major contributing factors.

Here in the United States, 94% of female characters on television are thinner than the average American woman (Gonzalez-Lavin & Smolak, 1995). This can be an issue because these women are frequently portrayed as happy, attractive, and successful. Unfortunately, viewing thinness as the be-all-end-all actually can contribute to high body image dissatisfaction (Stice et al., 1994).

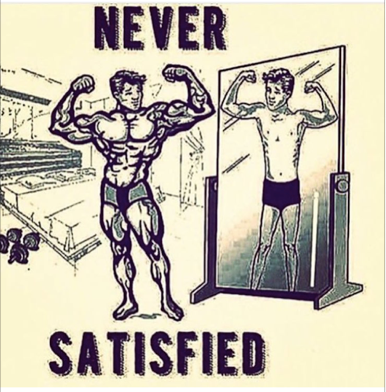

We like to joke that once you start lifting weights, you’re never going to be big enough in your own eyes. We chuckle because, for many of us, there is an inkling of truth to that.

But what if it gets taken to the extreme?

In a study conducted on 49 college-aged female women, 97.5% of participants reported that, following a 12-week supervised strength training program, they felt healthier and more fit; 51.2% indicated that their body image perceptions had improved (Ahmed et al., 2002). Meanwhile, 24.3% of participants – approximately one in four – reported either neutral or negative responses to their body image after training.

And within the weightlifting community, particularly amongst men, muscle dysmorphia (MD), a subcategory of BDD, is a syndrome in which individuals believe that they are of very small musculature (Choi et al., 2002). This syndrome is highly correlated with body image, and those with MD are preoccupied not only with gaining muscle but also with keeping bodyfat levels low.

Negative emotions associated with BDD include social anxiety, impaired self-esteem, and the avoidance of social events (Rumsey & Harcourt, 2004). This is no bueno.

Interestingly, distorted body image oftentimes has little to no relation to how an individual actually looks; his or her perception of the physical self is heavily influenced by cultural ideals. Social comparison theory suggests that women judge their own appearance by comparing themselves with societal definitions of beauty as depicted by mass media (Festinger, 1954). As well, this is strongly correlated with eating disorders in women (Brown et al., 1989).

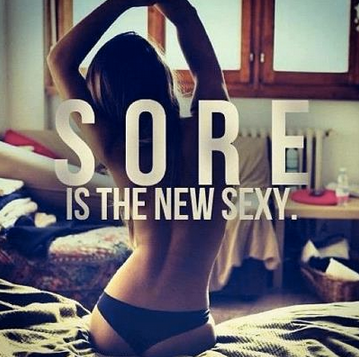

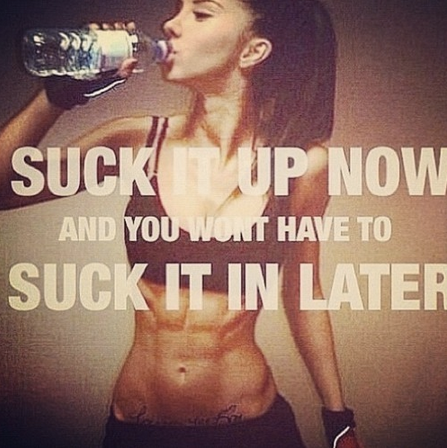

What’s “fitspo” got to do with it?

Ostensibly, the purpose of “fitspiration,” or “fitspo” – fitness inspiration – is to motivate others to pursue a healthier lifestyle. This has become a wildly popular movement in recent years; a search of the hashtag #fitspo on Instagram yields over 21.5 million (and counting!) different posts. And while the intentions may seem innocuous, most of the pictures associated with “fitspo” consist of younger women who are lean and muscular. This can be troublesome because this can lead many individuals to believe that the only way to be considered fit and healthy is to look strong and have low body fat levels.

There is a positive correlation between time spent on the Internet and body dissatisfaction in adult and adolescent women (Bair et al., 2012). In fact, a study on 130 female undergraduate students earlier this year found that exposure to fitspo led to more negative body image, lower state appearance self-esteem, and negative mood (Tiggemann & Zaccardo, 2015).

To an extent, attempting to manipulate our body shape and size is normal. We exercise to stay in shape, we eat well to maintain our trim figures. But BDD takes it to the extreme, and fitspo isn’t helping.

What can we do about it?

Just because we’re alive in 2015 doesn’t mean that we’ll all become victims of BDD. I argue that it’s entirely possible to be present in this world and still maintain a healthy body image. Here are some actionable steps to take.

Focus on what you do like about your physical self rather than what you don’t.

Comparison is the thief of joy. We all know this. Yet it’s entirely too common to envy other people’s impossibly tiny waist, bootylicious badonkadonks, and shredded abs while completely overlooking our own assets. I can guarantee you, though, that others are looking at you and admiring your body parts (maybe your incredibly strong and muscular legs or your broad shoulders) at the exact same time.

Can I challenge you to do something? Stand in the mirror and just find one part of yourself that you like. Start there. Yes, it may be uncomfortable, and yes, it may take you a few minutes at first, but try to focus on the positives.

Me? I like my nose. Haha. Seems petty, right? I’ve got a tiny little button nose with an even tinier nose piercing that most people don’t even notice. But it’s proportional to my face and it’s very, ah, “me”. I like that. And it’s a solid starting point.

Consider limiting your social media exposure.

Based on study findings, it seems to make sense to recommend that individuals limit their exposure to social media where they may be able to view “fitspiration” images and posts. Maybe if that fitness celebrity on Instagram who regularly posts soft pornography under the guise of “fitness” stops showing up on your newsfeed, you can start to feel a little better. Unfollow, unfollow, unfollow. Bye, Felicia.

Change the way you speak to yourself.

I feel painfully granola just typing this out, but how true is it that we tend to use some pretty horrible language with ourselves? The fact of the matter is, we don’t put ourselves in a position for positive growth if we’re too busy shaming ourselves and calling ourselves awful names. And how can we be expected to feel good about ourselves if we’re not being compassionate and loving?

“You’re fat, unworthy, and useless” – these thoughts have to go. Replace them with words like “strong” and “capable”. You may not believe it about yourself now, but sometimes, you have to fake it ’till you make it.

Stop expecting to be perfect.

It’ll backfire. Perfection is not real and it’s elusive. This may seem counterintuitive, but there’s a lot of forward progress that can happen when you lean into your mistakes and embrace them as part of life.

Rather than looking a specific way, then, strive to feel a certain way.

Exercising with the goal for health rather than weight loss can contribute to positive body image (Cash et al., 1994).

Whereas before, I exercised primarily to lose weight, stay small, and run away (quite literally) from body fat – which, by the way, eventually backfired in a bad way – I now workout to feel confident, relieve stress, and clear my head. Oh yeah, and to get strong as hell, of course. Because obviously.

It feels good to feel good, doesn’t it? And ultimately, that’s what we all want.

Take the emotion out of the equation.

As I write this, I am currently 10 days out from stepping on stage in my next bikini competition. I’ve been dieting for a few weeks now, and this is the lightest and leanest I’ve been in years. Objectively, I know this. The numbers say so, and my friends and family echo the same sentiments. Yet when I look in the mirror, I just don’t see it.

The difference this time around, though, is that I can recognize that, precisely because I’m in the throes of contest prep, I almost necessarily have a distorted view of myself. I don’t “feel” lean per se, but I know that I am.

I couldn’t find anything to support the following statement of mine in the scientific literature, so take it with a grain of salt if you please, but here’s what I believe: it’s entirely possible to look in the mirror, recognize that you’re not seeing yourself objectively, and not internalize any thoughts you may have. The key is to be able to identify when this is happening.

A certain degree of body dysmorphia is normal and expected when losing bodyfat – particularly when you’re trying to get contest lean. So despite what others are saying, you may feel as though you still have a long ways to go. This is when it’s critical to rely on other, more tangible measures of progress, such as body circumference measurements and scale weight rather than pictures alone.

When you can take your emotions out of the equation, it becomes a whole lot easier to keep plugging along on your merry way.

My favorite quote to support this comes from my friend Coach Stevo:

View scale weight [or body measurements or your physique] with as much emotion with which you’d count the number of white cars in a parking lot.

You are not defined by your body.

References

Ahmed, C., Hilton, W., & Pituch, K. (2002). Relations of strength training to body image among a sample of female university students. J Strength & Cond Res, 16(4):645-8.

Bair, C.E., Kelly, N.R., Serdar, K.L., & Mazzeo, S.E. (2012). Does the Internet function like magazines? An exploration of image-focused media, eating pathology, and body dissatisfaction. Eating Behaviors, 13:398-401.

Brown, T.A., Cash, T.F., & R.J., Lewis. (1989). Body image disturbances in adolescent female binge-purgers: A brief report of the results of a national survey in the U.S.A. J Psychol Psychiatry, 30:605-13.

Cash, T.F., Novy, P.L. & Grant, J.R. (1994). Why do women exercise? Factor analysis and further validation of the reasons for exercise inventory. Percept Mot Skills, 78:155-9.

Choi, P.Y., Pope, H.G. Jr., & Olivardia, R. (2002). Muscle dysmorphia: a new syndrome in weightlifters. Br J Sports Med, 36(5):375-6.

Festinger, L. (1954). A theory of social comparison processes. Human Relations, 7:117-40.

Gonzalez-Lavin, A., & Smolak, L. (1995). Relationships between television and eating prbolems in middle school girls. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the Society for Research in Child Development.

Mabe, A.G., Forney, K.J., & Keel, P.K. (2014). Do you like my photo? Facebook use maintains eating disorder risk. Int J Eating Disorders, 47:516-23.

Rumsey, N., & Harcourt, D. (2004). Body image and disfigurement: issues and interventions. Body Image, 1(1):83-97.

Schwartz, M.B., & Brownell, K.D. (2004). Obesity and body image. Body Image, 1:43-56.

Stice, E.,M., Schupak-Neuberg, E., Shaw, H.E., & Stein, R.I. (1994). Relation of media exposure to eating disorder symptomatology: An examination of mediating mechanisms. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 103:836-40.

Tiggemann, M. & Zaccardo, M. (2015). “Exercise to be fit, not skinny”: The effect of fitspiration imagery on women’s body image. Body Image, 15:61-7.

Yamamiya, Y., Cash, T.F., Melnyk, S.E., Posavac, H.D., & Posavac, S.S. (2005). Women’s exposure to thin-and-beautiful media images: body image effects of media-ideal internalization and impact-reduction interventions. Body Image, 2(1):74-80.