Willpower is Not the Answer to Sustainable Weight Loss

Every now and then, I have a reader or a client whose body seems incredibly resistant to losing bodyweight. No matter how low we drop their calories relative to their bodyweight, regardless of how high their dietary adherence, and irrespective of how well they manage their sleep and stress, there is no fat loss progress to be made.

What’s the issue? Is it just that they’re still eating too many calories? Are they not trying hard enough?

A new study has been accepted for publishing in the Obesity Society journal that I think many of you will be interested in. It’s titled, “Persistent metabolic adaptation 6 years after ‘The Biggest Loser’ Competition,” and I’ve highlighted the main points below.

What is Metabolic Adaptation?

Metabolic adaptation, also known as adaptive thermogenesis, is the phenomenon by which the body’s resting metabolic rate (RMR) is disproportionately affected due to changes in calorie intake. You can undergo numerous metabolic adaptations with a prolonged caloric deficit, making weight loss increasingly difficult. Conversely, when you consume more food above your typical baseline, the body can increase its metabolic rate to match your intake and thereby prevent, or mitigate, weight gain.

But in those who engage in crash dieting, the degree of metabolic adaptation is far more severe.

Methods

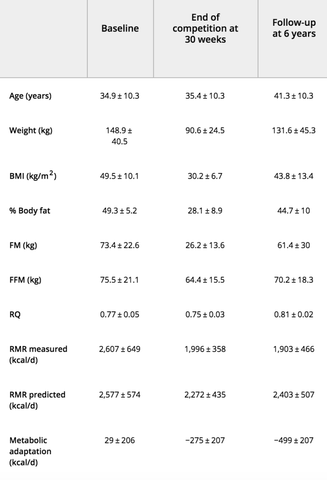

The study involved 14 out of 16 competitors from “The Biggest Loser” who agreed to participate. Dual energy X-ray absorptiometry (DEXA) was used to measure body composition, and RMR was calculated via indirect calorimetry at three different time points: the start of the competition, the end of the competition (30 weeks later), and six years after the fact.

Results

At the end of the competition, average bodyweight was decreased by 58.3kg, and RMR was reduced by 610 kcal/day. However, six years later, 41.0 of the 58.3kg was regained, RMR was decreased 704 kcal/day below baseline, and metabolic adaptation was measured at -499 kcal/day.

See the table below to view the results.

Notice how the participants gained back almost all of the weight that they’d lost. Their body fat percentage, more importantly, was almost back to their starting point. And their RMR was actually below what it was at the end of the competition.

What This Means for All of Us

The participants in this study undoubtedly went through a unique experience that the vast majority of us will never have to go through. We also have to take into consideration the fact that we do not know the specifics of how they lived their lives in the six years after the show was done – what and how much they ate, whether or not they consumed sufficient protein, whether or not they resistance trained or stayed active in other ways. These are certainly all confounding variables that could have influenced the results.

Nevertheless, the numbers themselves are very alarming. Some of you may be disheartened, while others may be relieved that it’s not anything you’re doing wrong, per se.

On the flipside, don’t be too quick to use metabolic adaptation as a scapegoat for why you haven’t seen any body composition changes over the past several months. (Fun fact: I tried to do this once about six years ago, when the culprit was actually that I was simply eating too much food. I just didn’t want to own up to it and be confronted with actually having to do the work of consuming less; it was far easier to blame something else).

Make sure you’ve first ruled out all the other potential variables: calorie intake (Are you actually in a deficit?), macronutrient breakdown (Are you consuming sufficient protein?), sleep and stress management, training program specifics (Are you on a program based on progressive overload, or are you just going through the motions?), and overall consistency.

I’ve been saying for a long time that the thinking that all you need is enough willpower to elicit body composition changes is misguided, first and foremost, but also not helpful.

Lasting change is not about willpower.

I’ve tried white-knuckling my way to fat loss before – perhaps you have as well. The only thing that it did for me was make me rebound and pile on 25 pounds on my 5’2” frame in a span of less than three months. Then, because I still believed that it was all about willpower, I spun my wheels for five straight years, trying and failing to lose the weight over and over.

Relying on willpower in the long run is a losing strategy.

As well, if there’s an underlying physiological issue, don’t ignore it, and don’t try to push your way through it. You don’t “fix” metabolic adaptation by dropping calories even more and consuming a low-calorie diet for months and months on end; that may, in fact, exacerbate the problem.

Be patient.

If you do decide that you want to shed some body fat, be methodical about how you go about it. Mindlessly slashing calories left and right is irresponsible and could cost you in the long run. And while you want to rely on sustainable methods in order to achieve sustainable results, you also don’t want to drag out the process longer than needed. That means that you should prioritize fat loss for a few months, keep dietary adherence high, and then pull yourself out a caloric deficit within a reasonable timeframe.

Key Takeaway Points

- Sometimes, the answer is not “just try harder.” In fact, as a physique and strength coach, this is the last piece of advice that I ever give to a client. Typically, there’s something else going on – physiological obstacle, lack of skill (to meet dietary adherence), lack of knowledge, or generally not prioritizing goals – that, when addressed, can lead to some pretty drastic changes in the individual.

- It’s not always about having more self-control or willpower. Yes, there are instances whereby exerting willpower can help you make the better health decision – but these opportunities should be minimized whenever possible. Rather, relying on lifestyle changes and habits is a far more effective long-term strategy. Utilizing self-control should be reserved for special situations and done sparingly.

- The harder you diet, the higher the potential costs in the long run. Extremes are rarely ever worth it. If it’s not too late for you, avoid crash dieting. There are far more sustainable ways to go about achieving fat loss results.

- If you do have an extensive crash dieting history and your body is not responding to what should be a caloric deficit, a 3-month reverse dieting stint (or at the very least, keeping your calories at a healthy intake) probably will not be enough time for you to “fix” things. Note that the suppressed RMR that the participants in this study had six years after the conclusion of “The Biggest Loser.” If you’ve crashed dieted on and off for the past eight years, you’re probably looking at a recovery period of several years. I’ve worked with several clients before with extensive, extensive crash dieting backgrounds, and for them, not even a full year of reverse dieting (or even just staying out of a deficit and consuming ample calories) was enough time. Frustrating? Yes. But you can’t rush the process.